Tropical forests, and the Amazon rainforest in particular, are the most important source of biogenic volatile organic compounds (BVOCs) to the atmosphere. The species isoprene dominates these emissions. Isoprene is a reactive BVOC species that only live minutes to hours in the atmosphere before it reacts chemically with other compounds, contributing to the formation of ozone and aerosols. Thereby, isoprene plays a key role in atmospheric processes and may have a significant impact on global climate. However, we still know very little about the biological and environmental factors that regulate the emission of isoprene. Thus, model estimates are highly uncertain. Better understanding these factors is challenging not least because of the immense plant diversity of the Amazon region. It is still unclear, which plant species emit isoprene at all, and how these emissions vary seasonally and under extreme climatic conditions like El Niño events.

Measuring isoprene emissions

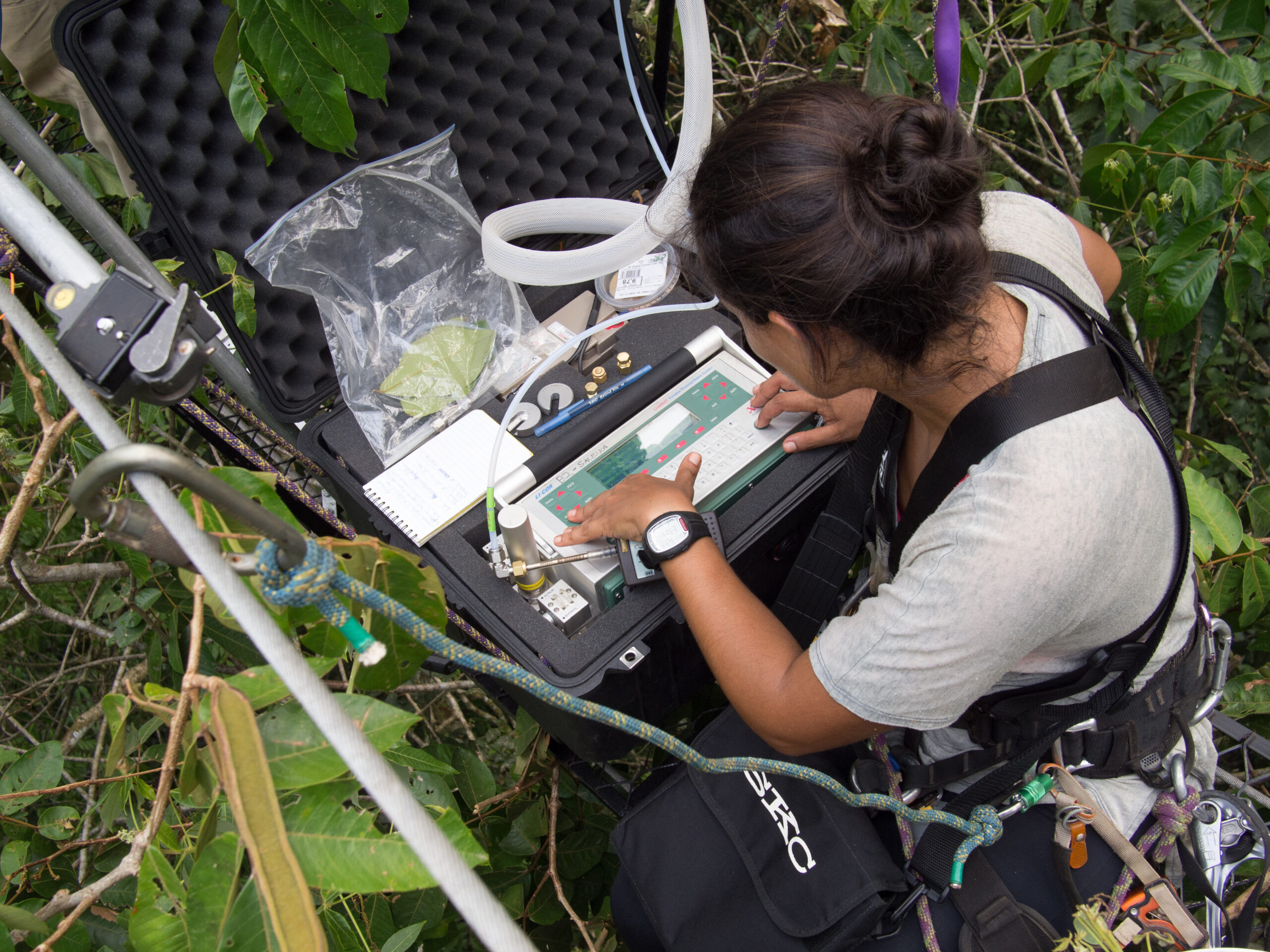

To address these uncertainties, Eliane Gomes Alves and her colleagues measured isoprene emissions at the ATTO 80-meter tower at eight heights in and above the canopy. They also observed 194 trees with a camera installed at the tower to track leaf phenology changes over time. Out of those 194 trees, the team observed 36 trees along a canopy walkway in detail with respect to leaf ages and phenology, and partially with respect to isoprene emissions of individual leaves. Overall, the team collected data across three years, including 2015, a year characterized by a strong El Niño with a heatwave and drought in the Amazon region.

The researchers found that isoprene emissions varied seasonally, with increased emissions during the dry season and dry-to-wet transition season, compared to the wet season and wet-to-dry transition season.

In addition, the team looked at the effect of the 2015 El Niño on isoprene emissions. Because tropical plants typically emit more isoprene at higher temperatures, they expected emissions to increase significantly during this period of extreme heat. However, the scientists found that the values were only slightly higher than during normal dry season. They argue that this is likely due to the stress plants experience due to the El Niño induced drought that likely offset the expected increase in isoprene emissions.

The effect of leaf age

As a next step, they looked at the isoprene emission capacity of leaves of different ages. They found that growing and mature leaves (1 to 6 months old) have the highest emissions, while young (up to 1 month old) and old (over 6 months old) leaves emit on average one third less isoprene. These results are in line with those from prior studies, but Eliane Gomes Alves and her colleagues were able to confirm it for more species.

Even though leaf phenology in the evergreen Amazon does not follow a well-defined seasonal pattern as in mid and high latitudes, many tree species in the Amazon still have a seasonal cycle. Trees tend to flush new leaves in the wet-to-dry transition season, leading to a substantially higher fraction of mature leaves in the dry season and dry-to-wet transition season. Since mature leaves emit more isoprene, the emission capacity of Amazonian leaves is highest during this time, peaking in October and November.

Finally, the scientists included their findings in the widely used Model of Emissions of Gases and Aerosols from Nature (MEGAN) to test if they could improve it, and what factors are most relevant. They found that the key factor in improving model predictions is to include the seasonal variation of isoprene emissions related to leaf age.

Eliane Gomes Alves et al. published the study Intra- and interannual changes in isoprene emission from central Amazonia Open Access in Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics.

Similar articles

Direct measurements of OH radicals are rare and difficult to achieve. However, since they react with BVOCs, Ringsdorf et al. inferred them from isoprene measurements at ATTO. To do so, they applied a technique called ‘Dynamical Time Warping’ from the field of speech recognition. Akima Ringsdorf et al. published the study “Inferring the diurnal variability of OH radical concentrations over the Amazon from BVOC measurements” Open Access in Nature Scientific Reports.

BVOC emissions in the Amazon have been studied for decades, but we still don’t fully understand when and under what conditions tree species or even individual trees emit more or fewer isoprenoids. To address this, Eliane Gomes Alves and her colleagues measured isoprenoid emission capacities of three Amazonian hyperdominant tree species.

Mosses and lichen appear to play a previously overlooked but important role in the atmospheric chemistry of tropical rainforests. A new study from Achim Edtbauer and colleagues shows that such cryptogams emit highly reactive and particle-forming compounds (BVOCs) that are important for air quality, climate, and ecosystem processes.

High-quality atmospheric CO2 measurements are sparse across the Amazon rainforest. Yet they are important to better understand the variability of sources and sinks of CO2. And indeed, one of the reasons ATTO was built was to obtain long-term measurements in such a critical region. Santiago Botía and his colleagues now published the first 6 years of continuous, high-precision measurements of atmospheric CO2 at ATTO.

Biogenic volatile organic compounds remove OH from the atmosphere through chemical reactions, which affects processes such as cloud formation. In a new study, Pfannerstill et al. reveal the important contributions of previously not-considered BVOCs species and underestimated OVOCs to the total OH reactivity.

Nora Zannoni and her colleagues measured BVOC emissions at the ATTO tall tower in several heights. Specifically, they looked at one particular BVOC called α-pinene. They found that chiral BOVs at ATTO are neither equally abundant nor is the ratio of the two forms constant over time, season, or height. Surprisingly, they also discovered that termites might be a previously unknown source for BVOCs.

Fungal spore emissions are an important contributor to biogenic aerosols, but we have yet to understand under what conditions fungi release their spores. Nina Löbs and co-authors developed a new technique to measure emissions from single organisms and tested this out at ATTO and with controlled lab experiments. They published their results in the Open Access Journal Atmospheric Measurement Techniques.

In a new study, Nathan Gonçalves and co-authors now wanted to find out if extreme climate events such as droughts influence leaf flushing, and thereby the average leaf age and photosynthetic capacity of the forest, and if is it possible to monitor more subtle changes associated with extreme events (compared to season changes) with satellites?

Pfannerstill et al. compared VOC emissions at ATTO between a normal year and one characterized by a strong El Nino with severe droughts in the Amazon. The did not find large differences, except in the time of day that the plants release the VOCs. They published their results in the journal Frontiers in Forest and Global Change.