Hello! My name is Camila Lopes. I’m a meteorologist working in the ATTO Project since 2020. It is part of my Ph.D. studies at the University of São Paulo, Brazil, under the supervision of Prof. Rachel Albrecht. I’m involved in a project to study the lifecycle of clouds and aerosols in the Amazon by measuring their properties in several locations. One of these locations includes the ATTO Tower and a new site assembled about 4-km away from the tower. The site is called “Campina”, which means “meadow” in Portuguese. Sandy soil and the lower trees compared to the surroundings, gave the site has this name. Seen from above, this region is like a hole of bare soil in the middle of a dense and endless forest. This is also what makes it an ideal location for a meteorological measurement setup that needs to look above the trees.

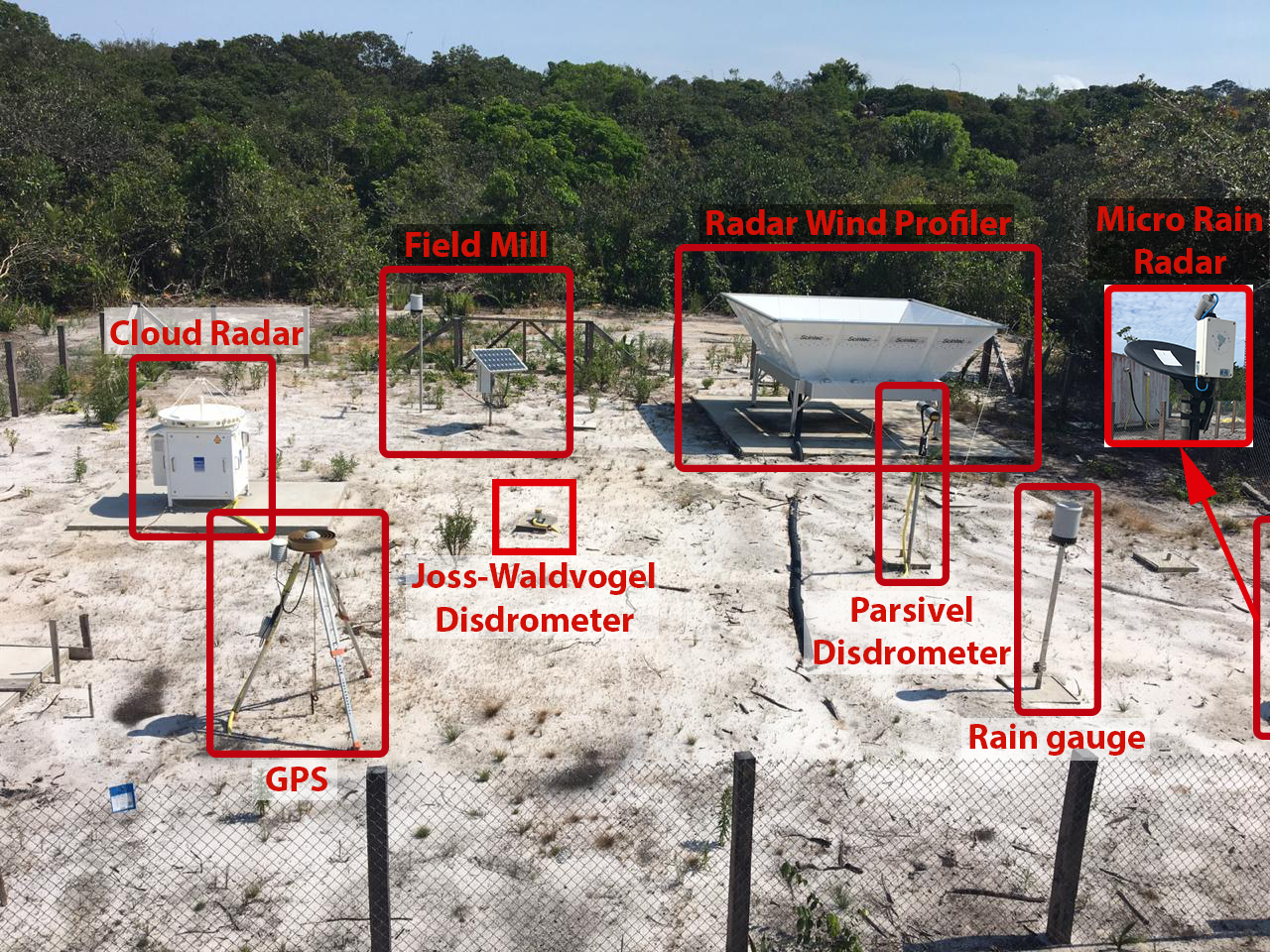

Since late 2019, two containers and several instruments were installed at Campina site. This includes three weather radars with distinct purposes: one for clouds, one for winds, and one for rain. These radars emit signal beams to the atmosphere above in a given frequency. Air particles sensible to that frequency scatter a fraction of it back, which the radar then receives and measures. This allows us to estimate the properties of these particles. It’s important to install radar in an open space like Campina to avoid beam blockage by trees and other interferences.

I’m responsible for the operation of the cloud radar, called MIRA-35C. The frequency of this radar is in the Ka-Band (35GHz, more specifically), a well-known band in the radar community for detecting cloud droplets and ice. Radars in this band can be also found aboard a satellite orbiting our planet, in a research aircraft, or on the surface, associated with field experiments around the world. A curious characteristic of this band is that it’s also really sensitive to insects. While filtering is necessary for cloud applications, the raw data can be quite useful for boundary-layer meteorology, since these insects fly only within this lower layer of the atmosphere. This is the first time that this type of cloud radar is installed in the middle of a tropical rainforest. So we’re really excited to see what we’re able to find and compare with other regions.

The instrument itself is basically the antenna mounted above a small container with an air-conditioner and a system with a computer that receives, pre-processes, and converts the raw signal to physical variables. These include reflectivity (equivalent to the number of particles in a sample volume), Doppler velocity (to know if the particles are going up or down) and others that help to identify what we measured. The computer is connected to a notebook inside the research container from where we control the radar. Our team installed MIRA during my first visit to the site in March 2020, right before the pandemic started in the region. It’s been running since then thanks to a small team of technicians that kept working at ATTO during the pandemic.

I was born and raised in the concrete jungle of São Paulo city and am 100% a big city person. Therefore, it was quite an experience for me to spend ten days in the middle of the forest hearing birds and insects instead of cars and sirens. Besides the heat and humidity making me sweat forever and ruining my hair, I actually enjoyed the visit. This was probably because I didn’t have the “full experience”. I didn’t find snakes or huge spiders, I didn’t spend the whole day away from an air-conditioner, and I didn’t climb the 325-m tower. I’m so afraid of heights that going to the base of the tower and looking up was enough of adventure for me. But, who knows… maybe next time I’ll find the courage to do it. 🙂

Camila published a Portuguese version of this blog post on her own website: cclopes.me. / Camila publicou uma tradução em português deste blog em seu próprio site: cclopes.me.