Walking in the Amazon rainforest is exciting. You are surrounded by a seemingly impervious mix of trees and understory plants. The air is hot and humid and you hear sounds of birds, insects, frogs and occasionally the awe-inspiring chanting of the howling monkeys. But rarely one is able to see animals, even though they are present in abundance. As the forest is so dense, you always walk in the shade of the canopy above you. Wherever you look you see tree stems in various sizes, lianas and shrubs. What at first glance appears to be the surface of the tree stem, liana, or shrub, is upon closer inspection overgrown with various organisms. These organisms are collectively called cryptogamic organisms. Bryophytes, which is an umbrella term for moss like organisms, and lichens, are important parts of this cryptogamic cover. Once you are accustomed to seeing them and not mistake them anymore for tree bark you start seeing them everywhere. It is actually hard to find a surface in the rainforest which is not covered by cryptogams.

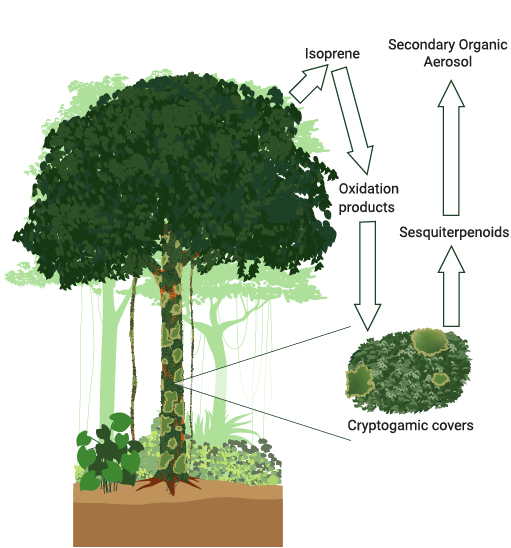

Tropical rainforests are by far the most important source of biogenic volatile organic compounds (BVOCs) worldwide. These emissions influence the oxidation capacity of the atmosphere and are important for secondary organic aerosol formation. Knowledge of the amounts and sources of BVOC emissions is therefore important for modelling climate change.

To date, BVOC emissions from tropical forests are assumed to be originating from the leaves of trees. So, we wondered whether the extensive cryptogamic cover on tropical trees itself might play a role in the emission of BVOCs.

Our research regarding this question was carried out at the ATTO site, which is a remote pristine Amazon rainforest site located around 150 km northeast of Manaus (Brazil). Getting there from Manaus is already an adventure in itself. The journey consists of dirt roads and several hours of boat travel and takes at least half a day. During the wet season, when the water level in the river is high, the boat ride shortcuts through a flooded forest which is always a highlight of the trip. Upon arrival at the ATTO camp, you are greeted by the local Brazilian staff who keep the site running. Facilities are basic but very enjoyable. It is quite surprising how cozy it can be to sleep in a hammock while listening to the sounds of the rainforest.

In order to investigate the BVOC emissions from bryophytes and lichens, we set up a cuvette system. We placed three glass cuvettes in the rainforest understory adjacent to a measurement container, which contained our mass spectrometers. Ambient rainforest air was fed at a constant rate through all three cuvettes. One cuvette always remained empty to serve as the background cuvette whereas the other two were filled with bryophyte or lichen samples. After the ambient rainforest air had passed through these cuvettes, it was directed towards our mass spectrometer (PTR-ToF-MS) to measure the concentration of BVOCs in this air. Together with the known flow and the background cuvette we were able to calculate BVOC fluxes from our samples.

We wandered off the tracks of the ATTO site and ventured into the understory of the rainforest to get pristine samples of bryophytes and lichens. This was always exciting and sometimes nerve-racking as stories of jaguar sightings and poisonous snakes came into our minds. Snakes are nevertheless the real danger here as you need to be rather lucky to ever see a jaguar in the wild. So, when walking into the rainforest we moved cautiously and were supported by locals. We selected samples, which are common and widespread throughout the Amazon so that upscaling to the whole Amazon is justifiable. Owing to the great biodiversity and the abundance of similar-looking cryptogams we often spent some hours walking through the rainforest before we could be sure to get a good sample. When we had located a suitable sample, we carefully removed it from the tree bark with as little damage as possible, transported it to the lab and cleaned it from remaining impurities. Afterward, the sample was measured in the cuvette flux system described above.

To our surprise, we found that lichens and especially bryophytes emit considerable amounts of sesquiterpenoids. These are compounds with 15 carbon atoms (C15) arranged in various configurations. These molecules react rapidly with ozone to form oxygenated compounds and particles in the air. When we extrapolated these emissions to the scale of the Amazon rainforest, we were amazed to find out that emissions of sesquiterpenoids from cryptogams were similar in amount to emissions from the trees.

This turned out not to be the only surprise that these inconspicuous organisms had in store. They did not only emit sesquiterpenoids but were taking up oxidation products of isoprene (isoprene is the most abundantly emitted BVOC in the rainforest). This implies that loss of these compounds does not only happen via reactions with radicals (like OH and ozone) in the atmosphere, because loss via cryptogams uptake can be important.

This work was only possible by working together with experts in other fields of science. My background is physics and atmospheric chemistry and for this project, I worked together with experts in biology with expertise on cryptogams. It was fascinating to learn about these often-overlooked organisms which seem to play an important role for atmospheric chemistry.

Since I learned more in detail about them I started seeing them everywhere I go on trees, rocks, walls or even on pavement if you look carefully. So watch out for these “hidden” organisms on your next walk – maybe you will see them in a different light.